Fifty-three years ago today, I was 10 years old, holding a ladder for my uncle who was painting the eaves of the barn on Wightman Street in Ashland. We were listening to the radio, some pop music on the local a.m. station. I had a reputation, even then, of being a dreamer. Uncle kept asking me, "Are you still holding on?" In my faraway thoughts, his voice had a tinny quality, almost a tinkle. And yet I know for a fact that his voice was a basso profundo.

"Yeah," I kept saying, thinking about the new school year, my homework (as yet undone) and the thought of dinner, which was always preferrable to holding a ladder. "Uh-huh."

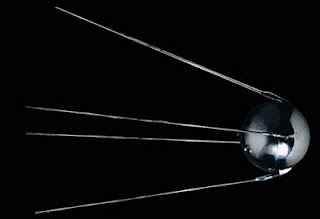

Suddenly, the announcer broke in to say that the Ruskies, the Soviets, had launched a satellite they called Sputnik that was orbiting the earth as we stood there under the eaves. The earth! Ruskies! And what was a Sputnik? Good Lord. Uncle climbed down from the ladder and told me to fetch my father, a wireless pioneer and one of the first electronic engineers. I ran up the path to the big house, past my playhouse--now used to store car parts--and into the warm kitchen to find Dad. He was sitting at the table with my grandfather, tipping back a beer.

I burst in to their conversation, unable to contain my excitement. "What's a satellite? What's an orbit? Is it like an obit?" Dad put down his beer. "Why do you ask, kitty cat?" He asked in his kindly, calm engineer's voice. I excitedly explained that we heard a report on the radio and that something called Sputnik was circling the earth in an orbit.

Dad walked over to the Blauplunct radio sitting on the kitchen counter and switched it on, punching the buttons to scan the airwaves. Sputnik was on every station. I looked at my grandfather, who suddenly looked very old, indeed. He looked up at my Dad, who was listening intently to the reports. Dad sighed. "It's going to change everything," he said. "They're ahead of us, now."

By this time, Uncle had washed up and abandoned the barn eaves entirely. He walked in, slamming the screen door as he went. "What's all this mean, Glen," he asked my father, the acknowledged genius of the bunch. Dad just shook his head and repeated, "Everything is going to change now." That night, we got out our field scope and looked skyward. I saw a shooting star, which seemed to be falling casually onto the horizon. "That's it," Dad said with finality. "That's Sputnik." Sputnik was in orbit for 28 days before it fell to earth. All that's left of it now are a couple of "O" rings enshrined in the Space and Air Museum in Washington, D.C. My father and his amateur radio buddies kept tabs on it as it circumnavigated the space around earth. I sat on my father's workbench and heard the scratchy space sounds with intermittent beeps. We watched it every night as it made its heavenly transit. Dad would always sigh heavily and say, "That's it."

About 20 years ago, I visited Kazakhstan, not far from where Sputnik was launched. It was not at all as I had imagined that day 30 some odd years earlier. It turned out that Kazakhstan was not a shiny amusement park with 50s style chrome rockets; rather, it was a windswept high desert, a bit like Yucca Mountain in Nevada. Nothing over a foot tall grew there, near Polygon, the Soviet nuclear test site. Sand was everywhere--in the air, on the makeshift table tops where we ate, under the elaborate hats the Kazakhis wore, sifting out of our notebooks, everywhere.

Polygon reminded me of a horror movie I secretly saw with my cousin at the Varsity Theater when she was supposed to be supervising me. In the movie, no one was really alive, they were zombies who moved jerkily to strange music as they whirled around the dance floor of an abandoned resort that once bustled on the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Walking dead, they were, just like these proud and beautiful central Asians who looked remarkably like Native Americans. Some of the Kazakhis had birth defects. Others were afflicted with cancers unknown to this high altitude tribal people who rode sturdy little ponies outfitted with wooden saddles.

But in 1957, my father was the only person in the family who understood what the launch of the first satellite meant. The cold war was about to heat up. Spies were going to use satellites. Broadcast would become dependent on satellites. Sputnik would also accelerate the age of computer communications. Soon after Sputnik's glory, my father taught me the phrase electromagnetic pulse. He said it might be the end of civilization, the way things were going. Decades later, we would be calling on IPhones, e-mailing Europe on laptops, reading books on Kindle. His precious telegraph key would go practically extinct. He sighed wearily. "What's it mean?" he asked rhetorically. "Everything. Everything is about to change."

No comments:

Post a Comment